Four Ancient Chinese Poems On Tea and One Symphony

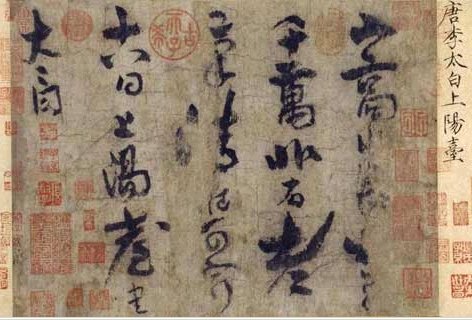

Calligraphy by Tang Dynasty poet Li Bai, public domain.

While sitting at home and finding comfort in tea during this pandemic health crisis, I have been thinking about the ancient nature of Chinese tea drinking. One of my favorite things about Chinese tea appreciation is its long storied tradition from ancient China until today.

Feeling Connected to Past Pandemics

Trying to stay healthy and safe during a health pandemic, however, also has connected me to other ancient ideas: surviving a health crisis.

I see a lot of people online rediscovering Boccacio’s 14th century “The Decameron”, the fact that Shakespeare and Issac Newton had to wait out the plague in confinement, or the 18th century book “A Journal of the Plague Year” written by Daniel Defoe.

There’s definitely something fascinating about how living during a contemporary global pandemic health crisis makes you feel connected to these ancient health crisis like The Black Death or bubonic plagues.

These ancient artifacts of disease and pestilenace are represented in my mind as such out of reach and outdated realities like Middle Age woodblock prints compared to our digital photographic present.

While sipping Chinese tea in my apartment in the Bronx, right in the middle of the COVID epicenter in America, NYC in the spring of 2020, I started wondering about previous ancient crisis in China, in particular, and where tea fit in there.

Tang Dynasty painting of women enjoying tea

Tea and Crises in Ancient China

Surely there were pandemics in ancient China and surely there are ancient poems, paintings, or literature writings about tea in relation to crisis. With ancient China flourishing in the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD), we are left with a rich amount of artifacts to rummage through and look for evidence and insights from ancient China.

In the book “Tea in China, A Religious and Cultural History” by James Benn writes: “The values associated with tea today—that it is natural, health-giving, detoxifying, spiritual, stimulating, refreshing, and so on—are not new ideas, but ones shaped in Tang times, by poets.”

But where to begin? I’m not a trained scholar in ancient Chinese poetry, artwork or literature. It takes me forever just to read an email in modern Chinese! It felt like googling in English to find artifacts about ancient Chinese crises and finding comfort in tea was like taking a handheld metal detector to the Pacific Ocean.

So I turned to some scholar friends, namely Dr. Christine Ho, Assistant Professor of East Asian Art at U Mass Amherst, and Dr. Alfreda Murck, lecturer in Chinese Art History at Columbia University. Both Dr. Ho and Dr. Murck mentioned the famous tea poem “Seven Bowls of Tea” by Lu Tong, written in the Tang Dynasty.

“Seven Bowls of Tea” is one of those texts that you see everywhere and its ubiquity almost renders it meaningless.

It is, the kind of text you see excerpted and quoted in every single book about tea and especially Chinese tea, and the kind of text you see hanging on the wall of many Chinese teahouses. Is it the “Live Laugh Love” of Chinese tea? Almost.

Anyways nevertheless it endures and has reached itself over 1300 plus years and halfway across the world into the consciousness of us here living our little lives in 2020 and into my own email inbox and computer screen in New York City, so it felt prudent to at least give it a new one over in the present moment.

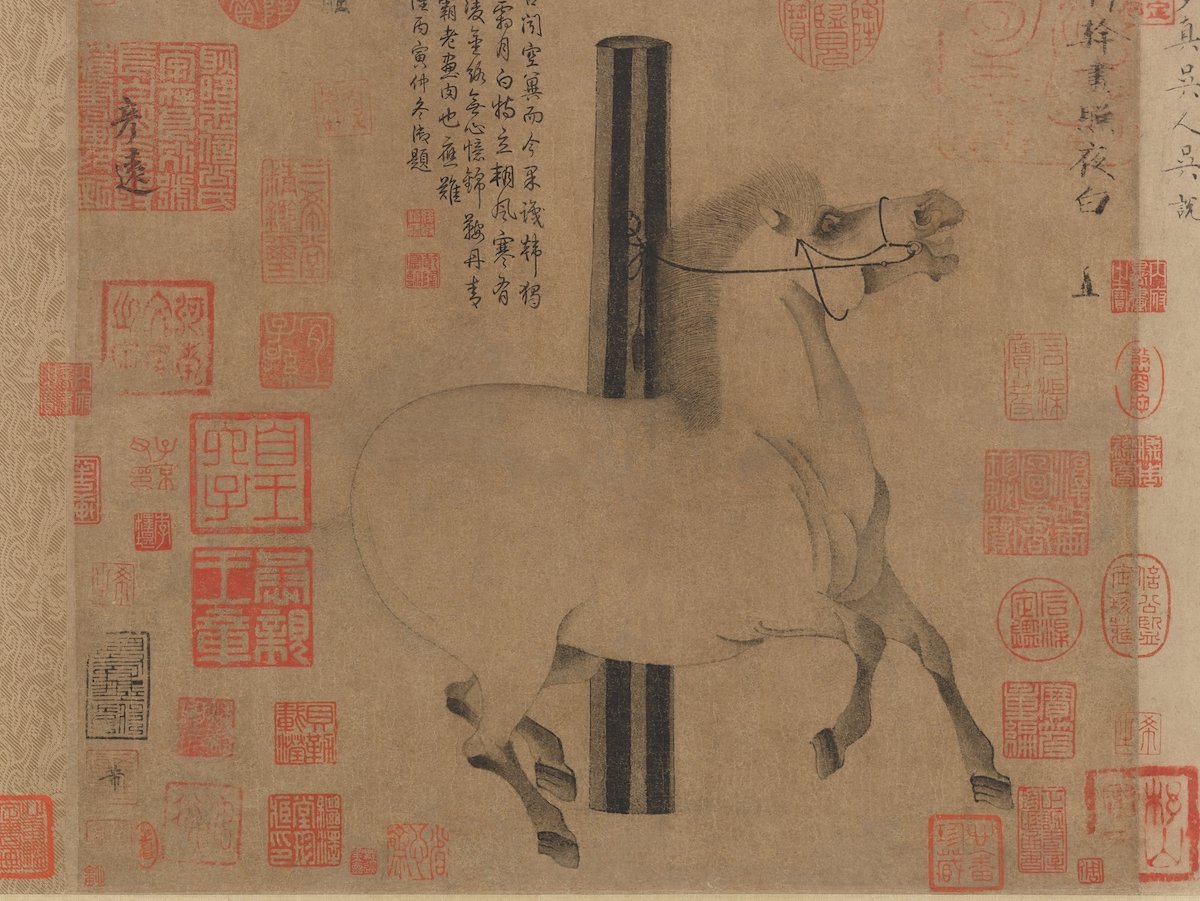

“Night Shining White” by Han Gan ca. 750 from the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection.

Poets, the “Cultural Engineers” of Ancient China

Poetry is a particularly important source for understanding tea in the ancient Chinese mind and culture. According to Benn, “Poets, as the cultural engineers of Tang times, had to invent a new world for tea to inhabit. Rather than create just a single cultural space, they made many, all of them interconnected to some degree.”

So I read a translation which Dr. Murck sent me via email:

SEVEN CUPS/BOWLS OF TEA

Lu Tong (790-835AD)

一碗喉吻润

二碗破孤闷

三碗搜枯肠,惟有文字五千卷

四碗发轻汗,平生不平事尽向毛孔散

五碗肌骨清

六碗通仙灵

七碗吃不得也,唯觉两腋习习清风生

One bowl moistens the lips and throat;

Two bowls shatters loneliness and melancholy;

Three bowls, thinking hard, one produces five thousand volumes;

Four bowls, lightly sweating, the iniquities of a lifetime disperse towards the pores.

Five bowls cleanses muscles and tendons;

Six bowls accesses the realm of spirit;

One cannot finish the seventh bowl, but feels only a light breeze spring up under the arms.

Loneliness, Melancholy, and Tea

The one line that really did stand out to me, reading at the present moment is the second line: “Two bowls shatters loneliness and melancholy/二碗破孤闷.”

As I began to contemplate the loneliness and melancholy that Lu Tong was describing I started connecting it to the loneliness many of us are experiencing as we are socially distant and isolated in our homes to prevent spread of COVID19 and help flatten the curve.

When Lu Tong mentions melancholy it also feels so presently relevant to the societal wide melancholy or at least the palpable sense of dread, anxiety, and sadness that filled the air in New York City with the staggering death toll and round the clock sound of ambulances as it became an epicenter for the global health pandemic.

Despite this meditation on loneliness and melancholy however, it is widely recognized that “the poem captures a spirit of serenity which we continue to associate with tea today,” according to George Van Driem’s “A Tale of Tea.”

While searching for different English translations of this second line “二碗破孤闷” in Lu Tong’s “Seven Cups of Tea” to compare to the first English translation I read, I came across a treasure trunk filled with shimmering jewels on the ocean floor of Google: the work of Steve W Owyang, his thorough and expert essays on this exact poem on Cha Dao (the most scholarly and nerdy of prominent asian tea appreciation blogs) and his own website Tsiophy.

That moment when your handheld metal detector actually finds a gem in the ocean is truly an exciting one and it made my day. I poured through all of Mr. Owyang’s copious research and expert English translations that he generously shared on his website. We even started up a correspondance and he kindly pointed me in the direction of some poems on his website.

Dr. Ho while also caring for a newborn baby (!), very generously pointed me in the direction of some books she thought me be helpful (that’s how I was able to find the previously quoted “Tea in China, A Religious and Cultural History”), and shared academic journal leads. Thanks to Dr. Ho sharing her academic pedigreed research abilities that really provided the backbone of this whole inquiry.

Ok so all that research, thinking, and reading has illuminated a few ancient Chinese poems all 1000+ years old, related to finding comfort and solace in drinking tea that I would like to share with you.

Textile with floral medallion, Tang Dynasty, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection.

Three Tang Dynasty Poems

There is of course a lot of scholarship on the historical and cultural context of each of these poems and what each word might mean in relation to that but I will let you just read them without commentary and see how it might speak to you in the present moment:

Joy at Seeing Tea Growing in the Garden

Wei Yingwu (Tang Dynasty 618-907 AD)

Its pure nature cannot be sullied,

When drunk it cleanses dust and worries. This plant has a truly divine taste,

And originates in the mountains.

After I have taken care of my responsibilities, I plant a tea bush in my uncultivated garden. It is happy to grow with the other vegetation And to speak with a person in solitude.

Translation in “Tea in China, A Religious and Cultural History”

A Song of Drinking Tea on the Departure of Zheng Rong

Jiaoran (Tang Dynasty 618-907 AD)

The immortal Danqiu abandoned eating jade elixirs,

Picking tea instead, he drank, and grew feathered wings.

The world is unaware of the Mansion of Eminent and Hidden Immortals,

People do not know of the Palace of Transmuting Bone into Clouds.

The Lad of Cloudy Mountain blended it in a gold cauldron;

How hollow the fame of the Man of Chu and his Book of Tea!

Late on a frosty night, breaking cakes of fragrant tea.

Brewed to overflowing, the pale yellow froth; I sip and am reborn.

Bestowed by the gentleman, this tea dispels my suffering,

Cleansing my mind from worry and fear.

Come morning, the emotions of the fragrant brazier remain.

Intoxicated still, we walk across the clouds reflected in Tiger Stream;

In high song, I send the gentleman off.

Translation by Steve Owyang

After Eating

Bai Juyi (Tang Dynasty 618-907 AD)

Having done eating I go to sleep,

Waking up, two bowls of tea.

Raise my head to see the sun’s shadows,

Already returned to being slanted in the southwest.

A happy person regrets the fast disappearance of daylight, A sorrowful person feels sick of the slow passage of time. Those without worries nor delight,

Simply let life be.

Translation in “Tea in China, A Religious and Cultural History”

And if after all that, you are like Charlene give me more ancient Chinese Tang poetry, I have more for you!

Mahler’s 9th Symphony manuscript from the Morgan Library Collection.

Gustav Mahler Also Inspired by Tang Dynasty Poetry!

In this month span when I’ve been working on this self-directed research paper (hahah, just me being me) I also learned from the New York Philharmonic Digital Mahler Festival that Gustav Mahler (Austro-Bohemian German speaking 19th-20th turn of the century classical music composer) himself was inspired by ancient Chinese Tang Dynasty poetry as a comfort to his own personal sorrows and crises.

He composed his 9th symphony (its a long story how this is counted as 9th symphony or not vs just symphonic song cycle), known as Das Lied von Der Erde based on inspiration from German translations of Tang Poetry! You can listen to the music here with a spoken introduction on the background before the music starts.

Ok so tell me what you think and how you felt reading these ancient Chinese poems about tea and what it means to you at the present moment while many of us are also turning to tea for comfort.